Click on any highlighted area for more information. All photos for this blog are from the internet.

I have always been skeptical of habituating wild animals to humans. I’ve seen the damage this has done to the bears in the National Parks in the 60s when I vividly remember traveling in Yosemite as a 12-year-old with my family. Dad encouraged us to crack our car windows to feed bread to the bears…and, so we did. We have home movies of this insanity. Over ten years later when I tent camped there again as an adult, bears were rummaging campgrounds to access the campers’ delicacies. That night armed rangers roamed our campsite tranquilizing the bears who were ripping open a Fiat convertible seeking store-bought food. The damage humans have done is evident. My third blog on Rwanda provided me with another great lesson about humans and wildlife.

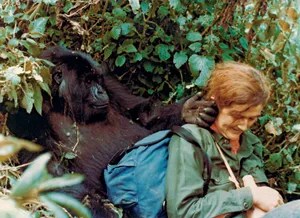

Now, 60 years later, what good would it do to habituate wild gorillas to humans in Rwanda and Uganda? Eventually, the reason became clear in the 1960s, when Dian Fossey, an American primatologist, did her research of the gorillas. Only about 250 lived in the wild in Rwanda at that time.

As I had said in my last blog, poachers where killing and capturing them at unprecedented numbers. In addition, villagers were encroaching into their habitat, and humans and their proximity to each other was a concern for disease transmission. As Fossey continued her research, she sought to protect the gorillas to prevent poaching and injuries from traps. When Fossey was tragically murdered in 1985, her 20-year effort to protect the gorillas continued and the gorilla population gradually increased. Ultimately, AWF (Africa Wildlife Foundation), the Fauna Preservation Society, and the World Wildlife Fund formed a consortium to bring various funds and initiatives under one tent and help fulfill Rwanda’s request to preserve the gorillas. The Mountain Gorilla Project, with AWF at the helm, focused on capacity-building, anti-poaching, and awareness-building. The project also worked to habituate mountain gorillas to tourist groups, and training Rwandan rangers about guiding.

By the end the 90s, tourism income was Rwanda’s largest earner of foreign exchange, making gorilla protection a national priority. During this time, a young conservationist and former Peace Corps volunteer from Zaire, Craig Sholley (today AWF senior vice president) joined the project. Rwanda now has over 1000 gorillas (10 families) and still growing.

On my Feb/Mar 2023 tour with OAT (Overseas Adventure Travel) we spent 90 precious minutes with Dr. Gaspard featured in the video below. Despite the efforts, snares are still an issue as hunters set traps to capture other small animals. So, with cooperation from the Rwandan government, veterinarians gradually habituated themselves with the gorillas so they could get close enough to provide care. Overtime, this was achieved. Click on this video of the Doctors in action.

The genetics separating the gorillas from humans is very small; we share 96-98% of the same DNA. Just as one human might be over protective of their child, the gorilla parent is no different.

Recently when a baby gorilla’s leg became snared in a poachers trap, initially the silver back would not let the gorilla doctors approach. After a few days the silver back understood and allowed the doctors to release and treat the baby with success.

As far as the gorillas are concerned, I now think differently about wildlife habituation. This human interaction has not only allowed medical treatment to occur, the gorilla population to grow, but also gorilla tourism to flourish which benefits the country and her people as well. A Win Win for all. Let’s be mindful of the balance of our precious home called EARTH.

Hey Sue, back in the day Craig Sholley, Amy Vedder and Bill Weber were my three science teachers in Butembo, North KIvu. I told you how Bill and Amy got advanced degrees and went to work with Dian Fossey at Karisoke and I knew that Craig was still somehow involved in wildlife conservation. Small world, no? Paul

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Paul, Yes, many of us RPCVs have gone on to do great things. You being one of them. I see you are using another email. Maybe there’s still a chance for you to add the other reply from my last blog. So much to share with so many. Thanks for always tuning in.

Susan, AKA Gowee Sue

LikeLike

FYI I posted this on my FB page.

Back in the day. A half century ago (and yes, I gag writing that!) in 1973 I was privileged to be recruited from PC/Niger (in the Sahara) to be the first Peace Corps Regional Representative in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). I was responsible for all Peace Corps activities in the then Kivu and Haut Zaire provinces, effectively the entire northeast corner of a country as large as the US east of the Mississippi River. My Area of Responsibility (AOR) covered 299,827 square miles. To put that into perspective, that is slightly larger than Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Delaware and Kentucky COMBINED. 50 years ago there were approximately 575 miles of paved roads in my entire AOR (including what roads were paved in towns). The road infrastructure, such as it was, consisted of unmaintained, single-track dirt paths with muddy potholes that literally swallowed Mercedes trucks let alone my Land Rover. I once ran across some Brits doing the trans-Africa thing from Algiers to South Africa who had taken 5 days to travel 100 km – 60 miles in the Haut Zaire/North Kivu provinces. I set up the first Regional Office in Bukavu at the southern end of Lake Kivu where the Ruzizi River flows south into Lake Tanganyika and forms the border with Rwanda and Burundi (I later set up a second office in Kisangani [ex-Stanleyville] where the African Queen was partially filmed). Two of my Volunteers ended up working with Dian Fossey and the mountain gorillas at Karisoke at the end of their tours. On cloudy nights I could occasionally see the glow from the Nyiragongo volcano near Goma at the north end of Lake Kivu. At the time (mid-1973) I had two Volunteers assigned to an Italian mission in Uvira where the river entered the lake. On my first site visit we drove to the Ruzizi and saw multiple crudely drawn signs showing people being eaten by crocodiles, a warning that the river mouth area was extremely dangerous due to the masses of crocodiles that gathered there because of all the dead bodies flowing down from Rwanda in the first of several genocidal massacres that took place between the Tutsis and Hutus over the years. Standing on top of my Land Rover we could see huge Nile Crocodiles lurking along the banks even though the massacres had ended some time earlier. It’s the stuff of nightmares. On a lighter note, it was an absolute hoot visiting the PCVs (a married couple) because at meals I spoke to the PCVs in English, the priests spoke to themselves in Italian, I spoke to the priests in French and the PCVs spoke to the priests in Swahili (PC/Kinshasa decided it would be more effective for them to have Swahili than French). Talk about lively, polyglot conversations!

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Sue, back in the day Craig Sholley, Amy Vedder and Bill Weber were my three science teachers in Butembo, North Kivu.I told you how Amy and Bill got advanced degrees and went to work with Dian Fossey at Karisoke. I knew that Craig had stayed involved in wildlife conservation. Small world, no? Paul

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it just keeps circling back around. So amazing. Thank you for staying in touch.

LikeLike

wow! Incredible! Amazing experiences Susan and Mauler66!

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you for writing Terri, we cannot let this important history on the outcomes go unnoticed. We must keep exploring and documenting what we see and what we have learned.

LikeLike